وضعت مومياء مصرية قديمة يبلغ عمرها 4 آلاف عام كبار خبراء الطب في مكتب التحقيقات الفيدرالي الأمريكي إف بي آي في حيرة لسنوات عديدة بعد أن فشلوا في تحديد هوية صاحبها منذ العثور عليها عام 1915.

A museum wasn’t sure whose head they had put on display. That’s when the F.B.I.’s forensic scientists were called in to crack the agency’s oldest case.

قام فريق من علماء الآثار الأمريكيين بحفر مقبرة دير البرشا المصرية القديمة والدخول إليها في ذلك التوقيت حيث عثروا فيها على رأس مومياء مقطوعة على تابوت من خشب الأرز.

In 1915, a team of American archaeologists excavating the ancient Egyptian necropolis of Deir el-Bersha blasted into a hidden tomb. Inside the cramped limestone chamber, they were greeted by a gruesome sight: a mummy’s severed head perched on a cedar coffin.

The room, which the researchers labeled Tomb 10A, was the final resting place for a governor named Djehutynakht (pronounced “juh-HOO-tuh-knocked”) and his wife. At some point during the couple’s 4,000-year-long slumber, grave robbers ransacked their burial chamber and plundered its gold and jewels. The looters tossed a headless, limbless mummified torso into a corner before attempting to set the room on fire to cover their tracks.

سمى الباحثون تلك المقبرة برقم "10 أ" وأكدوا أنها كانت المكان الأخير لاستراحة حاكم يدعى تحوتي نخت وزوجته، مؤكدين أن لصوص القبور تمكنوا من نهب حجرة الدفن وكل ما احتوت عليه من ذهب ومجوهرات، وقاموا بإلقاء جثة مقطوعة الرأس في زاوية قبل محاولة إشعال النار في الغرفة لتغطية آثار السرقة.

The archaeologists went on to recover painted coffins and wooden figurines that survived the raid and sent them to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in 1921. Most of the collection stayed in storage until 2009 when the museum exhibited them. Though the torso remained in Egypt, the decapitated head became the star of the showcase. With its painted-on eyebrows, somber expression and wavy brown hair peeking through its tattered bandages, the mummy’s noggin brought viewers face-to-face with a mystery.

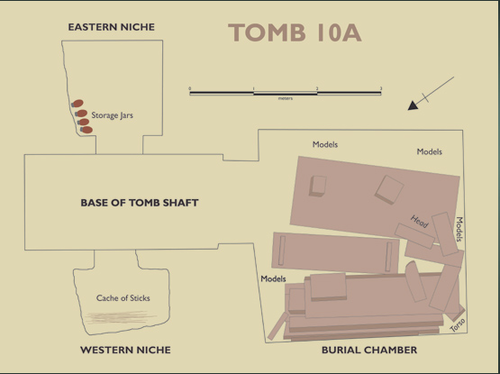

In 1915, workers with an expedition sponsored by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and Harvard University opened an entrance to Tomb 10A, where the severed head of Djehutynakht was found

“The head had been found on the governor’s coffin but we were never sure if it was his head or her head,” said Rita Freed, a curator at the museum.

واستعاد علماء الآثار توابيت مرسومة وتماثيل الخشبية نجت من الحريق وأرسلوها إلى متحف الفنون الجميلة في بوسطن عام 1921، وبقت بقية محتويات المقبرة قيد التخزين حتى عام 2009 عندما قرر المتحف عرضهم.

The museum staff concluded only a DNA test would determine whether they had put Mr. or Mrs. Djehutynakht on display.

“The problem was that at the time in 2009 there had been no successful extraction of DNA from a mummy that was 4,000-years-old,” said Dr. Freed.

Egyptian mummies pose a unique challenge because the desert’s scorching climate rapidly degrades DNA. Earlier attempts at obtaining their ancient DNA either failed or produced results contaminated by modern DNA. To crack the case, the museum turned to the Federal Bureau of Investigation

وأصبح الرأس المقطوع هو نجم العرض وقالت ريتا فريد، أمينة المتحف: "تم العثور على الرأس على نعش الحاكم، لكننا لم نكن متأكدين مما إذا كان رأسه أو رأسها".

وحاول موظفو المتحف إجراء اختبار للحمض النووي لتحديد هوية صاحب الرأس ولكنهم فشلوا، وقالت الدكتورة فريد: "كانت المشكلة أنه في عام 2009 لم يكن هناك نجاح في استخراج الحمض النووي من مومياء عمرها 4000 عام".

Objects left in Tomb 10A, which at some point had been ransacked by grave robbers.

The F.B.I. had never before worked on a specimen so old. If its scientists could extract genetic material from the 4,000-year-old mummy, they would add a powerful DNA collecting technique to their forensics arsenal and also unlock a new way of deciphering Egypt’s ancient past.

“I honestly didn’t expect it to work because at the time there was this belief that it was not possible to get DNA from ancient Egyptian remains,” said Odile Loreille a forensic scientist at the F.B.I. But in the journal Genes in March, Dr. Loreille and her colleagues reported that they had retrieved ancient DNA from the head. And after more than a century of uncertainty, the mystery of the mummy’s identity had been laid to rest.

وشكلت المومياوات المصرية تحديًا فريدًا للخبراء، نظرًا لأن المناخ الصحراوي في الصحراء يحطِّم الحمض النووي بسرعة، وتحولت القضية برمتها إلى مكتب التحقيقات الفيدرالي حيث حاول العلماء المتخصصون فيه استخراج المادة الوراثية من المومياء التي تعود إلى 4000 عام، مؤكدين أن نجاحهم سيضيف تقنية قوية لجمع الأحماض النووية إلى ترسانة الطب الشرعي، ويفتح أيضًا طريقة جديدة لفك شفرة الماضي المصري القديم.

What lies in Tomb 10A

Governor Djehutynakht and his wife, Lady Djehutynakht, are believed to have lived around 2000 B.C. during Egypt’s Middle Kingdom. They ruled a province of Upper Egypt. Though the walls in their tomb were bare, the coffins were embellished with beautiful hieroglyphics of the afterlife.

“His coffin is a classic masterpiece of Middle Kingdom art,” said Marleen De Meyer, assistant director for archaeology and Egyptology at the Netherlands-Flemish Institute in Cairo, who re-entered the tomb in 2009. “It has elements of a rare kind of realism.”

قال الدكتور أوديل لوريل، عالم الطب الشرعي في مكتب التحقيقات الفيدرالي: "بصراحة لم أتوقع أن ينجح ذلك لأنه في ذلك الوقت كان هناك اعتقاد أنه لم يكن من الممكن الحصول على الحمض النووي من الرفات المصرية القديمة"، ولكن في دورية جينيز في شهر مارس، ذكر الدكتور لوريل وزملاؤه أنهم استعادوا الحمض النووي القديم من الرأس.

The front panel of the coffin of Djehutynakht, which one Egyptologist calls, "a classic masterpiece of Middle Kingdom art."

The team that discovered Djehutynakht’s desecrated chamber more than a century ago was led by archaeologists George Reisner and Hanford Lyman Story. As they explored the cliffs of Deir el-Bersha, which is about 180 miles south of Cairo on the east bank of the Nile, they uncovered a 30-foot burial shaft beneath boulders. With the help of dynamite, they entered the tomb.

In their original reports the archaeologists said the dismembered body parts belonged to a woman, presumably Lady Djehutynakht. Dr. De Meyer suspected the head belonged to the governor and not his wife.

وبعد أكثر من قرن من عدم اليقين، استقر لغز هوية المومياء أنها للحاكم وليست لزوجته، وتوصل الباحثون إلى أن الحاكم تحوتي نخت وزوجته عاشا نحو عام 2000 قبل الميلاد، خلال عصر الدولة المصرية، حيث حكموا مقاطعة من صعيد مصر، وعلى الرغم من أن الجدران في قبرهم كانت عارية، تم تزيين التوابيت باللغة الهيروغليفية.

Missing facial bones

As Dr. Freed, the museum curator prepared the items from Tomb 10A for exhibition in 2005, she reached out to Massachusetts General Hospital. Its CT scan revealed the head was missing cheek bones and part of its jaw hinge — features that may have potentially provided insight into the mummy’s sex.

“From the outside you could not tell that the mummy had been so internally tinkered with,” said Dr. Rajiv Gupta, a neuroradiologist at Massachusetts General. “All the muscles that are involved in chewing and closing the mouth, the attachment sites of those muscles had been taken out.”

3D rendering of the mummy head made prior to tooth extraction.

Jennifer McGowan, Operations Manager for 3D Lab, MGH

لديهم الآن لغز آخر: لماذا كانت المومياء لديها هذه التشوهات بالوجه؟

إلى جانب ذلك قال الدكتور بول تشابمان ، وهو جراح أعصاب في المستشفى ، افترض الدكتور جوبتا أنه قد يكون جزءًا من ممارسة التحنيط المصرية القديمة المعروفة باسم "افتتاح حفل الفم". تم تنفيذ الطقوس حتى يمكن للمعاقين تناول الطعام والشراب والتنفس في الآخرة.

وقال الدكتور جوبتا "إنه قطع دقيق للغاية" ، مشيرا إلى الاستئصال الجراحي لجزء من الفك السفلي. "هناك بدقة بليغة لها وهو ما تفاجئنا به. كان شخص ما يقوم بالفعل بعمل استئصال الناتئ الإكليلي قبل 4000 عام."

كان بعض الأطباء وعلماء المصريات يشكون في أن المصريين القدماء يستطيعون القيام بهذه العملية المعقدة باستخدام أدوات بدائية.

لإظهار أنه من الممكن ، قام الدكتور جوبتا والدكتور تشابمان وجراح الفم والوجه والفكين بإزالة العظم على جثتين باستخدام إزميل ومطرقة. كانوا يحفرون بالازميل بين الشفتين واللثة خلف أسنان الحكمة ، وكانوا قادرين على إزالة نفس العظام المفقودة في الجمجمة المحنطة.

ومع ذلك ، بقي سؤال ما هى هوية المومياء.

They now had another mystery: Why did the mummy have these facial mutilations?

Along with Dr. Paul Chapman, a neurosurgeon at the hospital, Dr. Gupta hypothesized that they might be part of an ancient Egyptian mummification practice known as the “Opening of the Mouth Ceremony.” The ritual was performed so the deceased could eat, drink and breathe in the afterlife.

“It’s a very specific cut they made,” said Dr. Gupta, referring to the surgical removal of part of the mandible. “There’s a precision to it which is what we were surprised by. Someone was actually doing coronoidectomy 4,000 years ago.”

Some doctors and Egyptologists doubted that ancient Egyptians could perform that complex operation with primitive tools.

To show it was possible, Dr. Gupta, Dr. Chapman and an oral and maxillofacial surgeon performed the bone removal on two cadavers using a chisel and mallet. They drove the chisel between the lips and gums behind the wisdom teeth, and were able to remove the same bones missing in the mummified skull.

Still, the question of the mummy’s identity lingered.

سارقوا الأسنان

حدد الأطباء وموظفو المتحف أفضل فرصة لاسترجاع الحمض النووي عن طريق استخراج المولي للمومياء. وقال الدكتور تشابمان: "كان قلب السن هو المكان الذي كانت فيه الأموال". الأسنان غالبا ما تعمل كبسولات زمنية جينية صغيرة. استخدمها الباحثون ليخبروا حكايات أبناؤنا البشريين الذين يعود تاريخهم إلى عصور ما قبل التاريخ ، والذين يطلق عليهم اسم دينيسوفان ، بالإضافة إلى تقديم معلومات عن التاريخ الطبي لأشخاص ماتوا منذ أمدا طويلا.

وقال الدكتور شابمان: "كانت ميزتنا هي أن لدينا ثقب في الرقبة لأن الرأس قد تمزق".

انتزع فريق من الأطباء من مستشفى ماساتشوستس العام الأسنان من رأس المومياء في عام 2009 ، على أمل استخراج الحمض النووي.

لقد عرضوا نطاقًا طويلًا باستخدام كاميرا في مؤخرة الفم. ولن يتزحزح السن الأول الذي استهدفوه ، لذا تحول الدكتور فابيو نونيس ، الذي كان آنذاك عالمًا بيولوجيًا جزيئيًا في ماساتشوستس جنرال ، إلى ضرس أخر مختلف. التعرق ، ثبطت مع ملقط الأسنان ، وأعطتها بضع التذبذب ، ثم بضع التقلبات و "النتوئات" - لأنها كانت حرة.

"كان قلقي الرئيسي هوعندما قلت له : لا تسقطها ، لا تسقطها ، لا تسقطها" ، على حد قوله. بعد أن نجح في مناورة من الرقبة ، زفت الغرفة وحدقت على جائزتها.

وقال الدكتور فريد: "كان هذا يبدو وكأنه أسنان خالية تماما من التجويف." "أعتقد أنه ربما كانت السيدة ديجيوتي نيخت الذي توفي أثناء الولادة. كمجموع التخمينات ".

Tooth raiders

The doctors and museum staff determined their best chance of retrieving DNA would be by extracting the mummy’s molar. “The core of the tooth was where the money was,” Dr. Chapman said. Teeth often act as tiny genetic time capsules. Researchers have used them to tell the tales of our prehistoric human cousins called Denisovans, as well as to provide insight into the medical history of long dead people.

“The advantage we had is that we had a hole in the neck because the head had been torn off,” said Dr. Chapman.

A team of doctors from Massachusetts General Hospital extracted a tooth from the mummy head in 2009, hoping to extract DNA.

They snaked a long scope with a camera into the back of the mouth. The first tooth they targeted would not budge, so Dr. Fabio Nunes, who was then a molecular biologist at Massachusetts General, switched to a different molar. Sweating, he clamped down with dental forceps, gave it a few wiggles, then a few twists and “pop” — it was free.

“My main concern was: Don’t drop it, don’t drop it, don’t drop it,” he said. After he successfully maneuvered out from the neck, the room exhaled and gazed upon their prize.

“This looked like an absolutely cavity free, perfectly preserved tooth,” Dr. Freed said. “I thought maybe it was Mrs. Djehutynakht who had died in childbirth. Total speculation.”

الإف بى أى وأقدم حالة جنائية

لعدة سنوات ، حاولت فرق أخرى من العلماء دون جدوى للحصول على الحمض النووي من الضرس. ثم جاء تاج السن إلى الدكتور لوريل في الإف بى أى. بمختبره في كوانتيكو بولاية فيرجينيا ، عام 2016.

انضم الدكتور لوريل إلى مكتب التحقيقات الفيدرالي. بعد 20 عاما من دراسة الحمض النووي القديم. في السابق ، كانت قد استخرجت مادة جينية من دب كهف عمره 130 ألف عام ، وعمل في حالات للتعرف على ضحايا الحرب الكورية غير المعروفين ، وهو طفل عمره سنتين غرق على تيتانيك ومعه اثنان من أطفال رومانوف الذين قُتلوا خلال الثورة الروسية (على الرغم من أنها لم تكن قادرة على تأكيد ما إذا كان الشخص هو أنستاسيا الشهير).

في مختبر الإف بى أى. النظيف ، حفر الدكتور لوريل في قلب السن وقام بجمع القليل من البودرة. ثم قام بعد ذلك بحل غبار الأسنان لإنشاء مكتبة للحمض النووي (DNA) التى سمحت له بتضخيم كمية الدى إن إيه التي كانت تعمل معه ، مثل آلة النسخ ، وإحضارها إلى مستويات يمكن اكتشافها.

لتحديد ما إذا كان ما استخلصه هو الحمض النووي القديم أو التلوث من الناس الحديثين ، حلل كيف تضررت العينة. وأظهر علامات على وجود أضرار جسيمة ، مؤكد أنها كانت تدرس المادة الوراثية للمومياء.

لقد قام بتوصيل بياناتها إلى برامج الكمبيوتر التي قامت بتحليل نسبة الكروموسومات في العينة. وقال: "عندما يكون لديك أنثى ، يكون لديك المزيد من القراءة على X. عندما يكون لديك ذكر ، لديك X و Y".

برنامج البصق "الذكرى".

اكتشف الدكتور لوريل أن الرأس المقطوعة المحنطة كانت في الواقع تابعة للحاكم ديجيوتي نيخت. وأفلح في القيام بذلك ، كان يساعد في إثبات أن الحمض النووي المصري القديم يمكن استخراجه من المومياوات.

The F.B.I. ’s oldest forensic case

For several years, other teams of scientists tried fruitlessly to get DNA from the molar. Then the crown of the tooth came to Dr. Loreille at the F.B.I. ’s lab in Quantico, Va., in 2016.

Dr. Loreille had joined the F.B.I. after 20 years of studying ancient DNA. Previously, she had extracted genetic material from a 130,000-year-old cave bear, and worked on cases to identify unknown Korean War victims, a two-year old child who drowned on the Titanic and two of the Romanov children who were murdered during the Russian Revolution (though she was unable to confirm if one was the famed Anastasia).

In the F.B.I.’s clean lab, Dr. Loreille drilled into the tooth’s core and collected a tiny bit of powder. She then dissolved the tooth dust to make a DNA library that allowed her to amplify the amount of DNA she was working with, like a copy machine, and bring it up to detectable levels.

To determine whether what she had extracted was ancient DNA or contamination from modern people, she analyzed how damaged the sample was. It showed signs of heavy damage, confirmation that she was studying the mummy’s genetic material.

She plugged her data into computer software that analyzed the ratio of chromosomes in the sample. “When you have a female you have more reads on X. When you have a male you have X and Y,” she said.

The program spit out “male.”

Dr. Loreille discovered the mummified severed head had indeed belong to Governor Djehutynakht. And in doing so she had help establish that ancient Egyptian DNA could be extracted from mummies.

تماثيل للحاكم ديجيوتي نيخت ، باليسار ، وزوجته التي تم اكتشافها في القبر.

وقال بونتوس سكوجلوند ، عالم الوراثة في معهد فرانسيس كريك في لندن ، الذي ساعد في تأكيد دقة النتائج أثناء عمله كباحث في جامعة هارفارد: "إنها إحدى الكؤوس المقدسة للحمض النووي القديم لجمع بيانات جيدة من المومياوات المصرية". "كان من المثير جدا أن نرى أن أوديل حصلت على شيء بدا وكأنه يمكن أن يكون DNA قديم أصيل."

Statuettes of Governor Djehutynakht, left, and his wife that were discovered in the tomb.

“It’s one of the Holy Grails of ancient DNA to collect good data from Egyptian mummies,” said Pontus Skoglund, a geneticist at The Francis Crick Institute in London who helped confirm the accuracy of the finding while he was a researcher at Harvard. “It was very exciting to see that Odile got something that looked like it could be authentic ancient DNA.”

كشف التاريخ الوراثي للمومياء

وأظهر فحص الدكتور لوريل أيضا أن الحمض النووي للحاكم ديجيوتي نيخت حمل أدلة لغز آخر. لقرون من الزمان ناقش علماء الآثار والمؤرخون أصول المصريين القدماء ومدى ارتباطهم الوثيق بحديثيهم الذين يعيشون في شمال أفريقيا. ولدهشة الباحثين ، أشار الحمض النووي للميتوكوندريا الحاكم إلى أن أصله من جانب والدته ، أو من الهابلوغروب ، وكان أوراويا.

"لا أحد سيصدقنا أبدا" ، تذكرت الدكتورة لوريل قول زميلها جودي إيروين. "هناك مجموعة هابلوغرافية أوروبية في مومياء قديمة."

كان لدى الدكتور إيروين ، عالم البيولوجيا الإشرافية في وحدة دعم الحمض النووي (الإف بى أى) ، مخاوف مماثلة. وللتحقق من النتائج ، قاموا بإرسال جزء من السن إلى معمل هارفارد ، ثم إلى وزارة الأمن الداخلي ، لمزيد من التسلسل.

ثم في العام الماضي باسم الإف بى أى. عمل العلماء على تأكيد نتائجهم ، وذكرت مجموعة أخرى تابعة لمعهد ماكس بلانك لعلوم التاريخ البشري في ألمانيا أول عملية ناجحة لاستخراج الحمض النووي القديم من المومياوات المصرية. وأظهرت نتائجهم أن عيناتهم المصرية القديمة كانت أقرب إلى العينات الحديثة في الشرق الأوسط وأوروبا منها إلى المصريين المعاصرين ، الذين لديهم المزيد من السلالة الأفريقية لجنوب الصحراء الكبرى.

"كان في نفس الوقت" دانغ! نحن لسنا أولا "، قال الدكتور لوريل. "ولكننا أيضًا سعداء برؤيتهم لهذه السلالة الأوراسية."

وقال ألكسندر بلتزر ، عالم الوراثة السكانية في معهد بلانك ومؤلف في أول ورقة للحمض النووي للمومياء المصرية ، إن النتائج الجينية التي توصل إليها الدكتور لوريل تتلاءم مع ما وجده فريقه.

وقال: "بالطبع ، يجب على المرء توخي الحذر في استنباط الكثير من الجينوم المفرد والموقعين فقط".

كما أعرب الدكتور إيروين عن الحذر من الطريقة التي يفسر بها الجمهور نتائج فريقه ، قائلاً إن الحمض النووي للميتوكوندريا يوفر "مجرد لمحة صغيرة جدًا عن سلالة شخص ما".

Unraveling the mummy’s genetic history

Dr. Loreille’s examination also showed that Governor Djehutynakht’s DNA carried clues to another mystery. For centuries archaeologists and historians have debated the origins of the ancient Egyptians and how closely related they were to modern people living in North Africa. To the researchers’ surprise, the governor’s mitochondrial DNA indicated his ancestry on his mother’s side, or haplogroup, was Eurasian.

“No one will ever believe us,” Dr. Loreille recalled telling her colleague Jodi Irwin. “There’s a European haplogroup in an ancient mummy.”

Dr. Irwin, the supervisory biologist at the F.B.I.’s DNA support unit, had similar concerns. To verify the results they sent a portion of the tooth to a Harvard lab, and then to the Department of Homeland Security, for further sequencing.

Then last year as the F.B.I. scientists worked to confirm their results, another group affiliated with the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Germany reported the first successful extraction of ancient DNA from Egyptian mummies. Their results showed that their ancient Egyptian samples were closer to modern Middle Eastern and European samples than to modern Egyptians, who have more sub-Saharan African ancestry.

“It was at the same time ‘Dang! We’re not first,’” Dr. Loreille said. “But also we’re happy to see they had this Eurasian ancestry.”

Alexander Peltzer, a population geneticist at the Planck Institute and an author on the first Egyptian mummy DNA paper, said Dr. Loreille’s genetic findings fit well with what his team had found.

“Of course, one has to be careful to deduce too much from single genomes and only two locations,” he said.

Dr. Irwin also expressed caution with how the public interprets her team’s results, saying that mitochondrial DNA provides, “just a very small glimpse into somebody’s ancestry.”

- روابط التحميل والمشاهدة، الروابط المباشرة للتحميل من هنا

---------------------------------------------------------------

شاهد هذا الفيديو القصير لطريقة التحميل البسيطة من هنا

كيف تحصل على مدونة جاهزة بآلاف المواضيع والمشاركات من هنا شاهد قناة منتدى مدونات بلوجر جاهزة بألاف المواضيع والمشاركات على اليوتيوب لمزيد من الشرح من هنا رابط مدونة منتدى مدونات بلوجر جاهزة بآلاف المواضيع والمشاركات في أي وقت حــــتى لو تم حذفها من هنا شاهد صفحة منتدى مدونات بلوجر جاهزة بألاف المواضيع والمشاركات على الفيس بوك لمزيد من الشرح من هنا تعرف على ترتيب مواضيع منتدى مدونات بلوجر جاهزة بآلاف المواضيع والمشاركات (حتى لا تختلط عليك الامور) من هنا

ملاحظة هامة: كل عمليات تنزيل، رفع، وتعديل المواضيع الجاهزة تتم بطريقة آلية، ونعتذر عن اي موضوع مخالف او مخل بالحياء مرفوع بالمدونات الجاهزة بآلاف المواضيع والمشاركات، ولكم ان تقوموا بحذف هذه المواضيع والمشاركات والطريقة بسيطة وسهلة. ــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــسلامـ.

Post a Comment